I have a GREAT interview for you today. Asking a stranger random questions about their work can be a gamble — sometimes you get great answers, sometimes not. This time? Great answers.

I have a GREAT interview for you today. Asking a stranger random questions about their work can be a gamble — sometimes you get great answers, sometimes not. This time? Great answers.

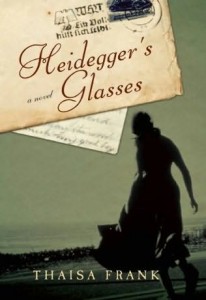

First, a little about the book, Heidegger’s Glasses:

Heidegger’s Glasses opens during the end of World War II in a failing Germany coming apart at the seams. The Third Reich’s strong reliance on the occult and its obsession with the astral plane has led to the formation of an underground compound of scribes—translators responsible for answering letters written to those eventually killed in the concentration camps. Into this covert compound comes a letter written by eminent philosopher Martin Heidegger to his optometrist, who is now lost in the dying thralls of Auschwitz. How will the scribes answer this letter? The presence of Heidegger’s words—one simple letter in a place filled with letters—sparks a series of events that will ultimately threaten the safety and well-being of the entire compound.

This one is definitely on my TBR list, but until then, I got a chance to ask author Thaisa Frank some questions about here work…

AotS: I am always fascinated by a writer’s process – how and when and where they write. Do you have any rituals around your writing? Particular places or times of the day that your write, music that you listen to or a schedule that you keep?

TF: About process: I tend to be a sprinter–that is, I mull over the story for a long time and collect fragments that have resonance until they’ve arranged themselves into a pattern and suggest the sequence and shape of the story. There are blank days in this process, during which I assure myself that the story is gestating and that I’m not just wasting time. (I’m never sure until the story manifests!)

Flaubert said: It’s not the pearls, it’s the way they’re strung together and I guess you might say that I collect the pearls very slowly and then work intensively until they’re strung into a viable necklace.

Rules and rituals: I generally have one writing rule that I stick to: I don’t take a break until 4:30 on weekdays. This means that I don’t meet people for lunch or schedule writing consultations with clients and I stay at my desk, or in a café with my computer, even if all I’m doing is staring. It’s kind of like being a shopkeeper. I may not have any customers that day but if I don’t show up, I won’t sell anything.

Places: In the mulling-over phase I can work in cafes. I like the ambient noise, the music in the background and the friends who stop to talk. But in the printing phase, I work in my studio–a quiet place with a lot of papers. I’m compulsive about the music and rhythm in my work, so I sometimes will print a page many times, just to see whether one comma should be taken out. I turn into a crazed type A maniac when I print and I wouldn’t want anyone to see me!

AotS: Do you generally plot the story in your head and know what you want to write when you sit down? Or do you just pick up a pen (or boot up the laptop) and let fly? Do you know when you begin how the story will end?

TF: I don’t know the plot when I begin a story. I start with a phrase, an image, a situation, and often a title. Sometimes I know the last phrases of a story without knowing what the story is about. I often start my stories in longhand and at some point work switch to my laptop. There’s always an exciting point in this process—the point at which the story seems to be an independent entity, outside my imagination. And then it begins to tell me what to do with it—what to take out, what to emphasize. It’s like catching on to a math problem or a puzzle. For me, this is on one of the most exciting parts of writing fiction.

AotS: You’ve published two previous books of short stories. How is it different, writing a full length novel? Do you think about the story differently?

TF: I start a novel the same way I start a story. That is, with an an image, a title, a sense of place, or a slightly surreal situation. For example: One element in Heidegger’s Glasses was a vision of a cobblestone street with gas lamps in an abandoned mine. There was a large room in this mine where people were writing letters to the dead. This image was on my mind when I started the novel. The room and the mine became populated with people. As did the title Heidegger’s Glasses. But a third of the way through, I had to begin to see how these strands related to a larger narrative arc that would carry the story through to the end. So this leds me to thinking about the plot. Short stories seem to resolve themselves on an intuitive level. In a short story, the pearls turn into something light, something that can be thrown in the air and land in a pattern. In a novel, two-thirds of the way through, I really have to think about “what comes next.”

AotS: I noticed in your bio that your style is frequently compared to legends and myths and fairy tales. Do you think you draw from myth and legend in your work?

TF: Fairy tales were the first stories I heard. And there was nothing more exciting to me than the phrase “Once upon a time.” I had a little viewer where I could insert discs of fairy tales and I remember looking at Red Riding Hood when she was alone in the woods. She was wearing her red cape and holding a basket. She was surrounded by pine trees. I thought she was real–alive in some alternate universe and this gave me the sense of being enchanted, under a spell, resonating with the imagination.

So I think that instead of drawing from anything specific in myth or fairy tale, I draw on that early sense of enchantment, a belief in the power of the imagination. When the writing is flowing, I feel often feel drawn into the kind of wonder I felt looking through the viewer as a child. Probably fairy tale elements emerge, but whether they do or not, I often feel the kind of excitement I can trace to my excitement when I heard fairy tales.

As for myth: I’m always grateful when someone sees a particular myth in my work, because I don’t intend it, yet might be drawing from it unconsciously. For example, one reviewer compared the heroine in Heidegger’s Glasses to Persephone, since she travels from the mine into daylight. I really appreciated that comparison, although I never would have thought of it.

AotS: Heidegger’s Glasses takes a very interesting angle on the Holocaust. Did this stem from a general interest in the subject, an interest in Hitler’s fascination with the occult, or was there something about this particular story that inspired you?

TF: I think I always tilt toward surrealism—that is, one impossible situation that happens in an ordinary world and is dealt with by an ordinary world. I often seen absurd, surrealistic situations in life–so I’m sure that surrealism chose me rather than the other way around.

However, the conscious catalyst for this story happened when someone at a Christmas party told me that Heidegger had once had a revelation brought about by his eye glasses. I’d been a philosophy student and read Heidegger, and had in fact been blown away by him. “Heidegger’s Glasses,” I thought. “That would be a good title.”

And so I started to write, just knowing that I wanted that title, and that Heidegger was an enigma because he was a great philosopher (he still has a great influence on philosophy, art, poetry, and architecture)—but also was a bumbling, addle-headed Nazi. I knew the glasses were going to be a metaphor for vision–or lack of it.

I think I’m a little naïve about my own process. Because I discovered that part of the story had been with me for sixteen years.

This is how I made that discovery: Sixteen years ago, I was in my studio and I heard a woman’s voice talking to me from the bottom of a mine. It was WWII, and she was trapped there, supervising people who wrote letters to the dead. I wrote several pages, realized the subject demanded a novel and stopped because I knew I could only write short stories. For years those pages kept popping out at me as though they were attached to springs—under tax forms, beneath drafts, in notes from my kids’ school about ecological lunches. I always read them with some regret–regret that I wasn’t a novelist and couldn’t grasp the whole story. And while I was writing the novel, they disappeared and I forgot about the sixteen page. But on the day I got the galleys of Heidegger’s Glasses, they popped out again. I re-read them and realized they were the DNA for the novel.

AotS: What’s your take on ebooks? Do you think it’s the latest craze, or do you think it will revolutionize books and writing? Or maybe somewhere in between?

TF: What I feel most sure about is that writing and publishing are in the second Gutenberg-Bible revolution. There’s a sense of disorientation in the publishing world. Both social networks and e-mail have changed the way we think about reading and writing. And so has being able to download books on computers and Nook and Kindle.

I think we don’t know yet what’s going to happen as result of that change: This became clear to me when my agent took me to a conference at the BEA about the e-book. There was a panel of agents, editors and publishers. And for every opinion one person had, someone else had the opposite.

I should add that I’m still very glad to have a good publishing house, a wonderful editor, a great in-house publicist and an extraordinary agent. They all have skills that are beyond me. As a writer, I feel mixed about the e-book. I like the book as a physical object. Yet Heidegger’s Glasses was in the top 100 of Kindle for a while. In any case, it’s a perilous but exciting time to be in the writing business.

AotS: How did you manage to avoid the current trend of throwing vampires or zombies into every story?

TF: So glad you asked! Enchantment (my next collection) has a story called The Loneliness of the Midwestern Vampire. I just couldn’t resist the trend.

Still, even The Loneliness of the Midwestern Vampire has a surrealistic tilt because it occurs in an ordinary town in the Midwest and the reality of the Midwest is larger than the reality of the vampire. The vampire doesn’t change this environment. In fact, he has to adjust to it.

AotS: Now, how about some either/or questions?

Mac or PC? MAC! (I’m one of the converted.)

Red wine or white? Dry Italian white.

Would you rather vacation on the beach or in the mountains? The beach, always, but best if there are mountains in the background.

Are you a night owl or an early bird? A night owl: I believe night is when stories fall from the sky.

Are you more of a tomboy or a girly-girl? ¾ girly girl ¼ tomboy